When I was in grade school, we were fed the now disputed notion that Eskimo languages, reflecting local concerns, had an unusually large number of words for snow. But nobody told us about the Inuit word iktsuarpok, which would have come in handy to describe one's behavior after putting in a call for a pizza delivery. Iktsuarpok “refers to the anticipation one feels when waiting for someone, whereby one keeps going outside to check if they have arrived.” So writes University of East London psychologist Tim Lomas in a cross-cultural linguistics study for the Journal of Positive Psychology.

Lomas's paper is entitled “Towards a Positive Cross-Cultural Lexicography: Enriching Our Emotional Landscape through 216 ‘Untranslatable’ Words Pertaining to Well-Being.” The 216 words in question, the first cull of Lomas's mostly Web-based searches, can of course be at least loosely translated, which explains the qualifying quotation marks around untranslatable. Lomas explains that the words “are deemed ‘untranslatable’ to the extent that other languages lack a single word/phrase for the phenomenon.” And let me tell you, his parents must be kvelling over his publication. The Yiddish word kvell, to use the many English words required in the paper, means “to glow with pride and happiness at the successes of others (often family members).” So much easier to simply kvell.

But can any mom and dad truly kvell without access to the word? Or is their emotional experience limited by the words available in their native language? “The existence of ‘untranslatable’ words pertaining to well-being implies that there are positive emotional states which have hitherto only been explicitly recognised by particular cultures,” Lomas writes. “However, this does not mean that people in other cultures may not have had a comparable experience. Yet, lacking a specific term for it, such people have arguably not had the opportunity to specifically identify that particular state, which instead thus becomes just another un-conceptualised ripple in the on-going flux of subjective experience.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In other words, his parents could indeed probably kvell even if they don't speak Yiddish. (Whether they got all the nachas they had coming is another question.) “However,” he writes, “the value of exploring ‘untranslatable’ words is that, if people are introduced to a foreign term, this may then be used to give voice to these hitherto unlabelled states.”

So let's give voice, using some of Lomas's excavated non-English words, to some hitherto unlabeled states and possibly enrich our emotional landscape.

Ever keep eating even when full because to do so was just so damn enjoyable? The Georgian word shemomedjamo describes this phenomenon. It's also the sound that comes out of you a few hours later. Portuguese has desbundar to capture becoming uninhibited while having fun. Bantu's even more specific mbuki-mvuki involves whipping off your clothes to dance. Hey, it's tough to dance in tight pants.

One of life's great pleasures (memorably captured in the movie The Shawshank Redemption) is drinking beer outside on a hot day, which is utepils in Norwegian. Drink too much and thereby come up with an ingenious plan, and you've committed the German Schnapsidee. Try to realize that plan, and your enemies will no doubt be filled with Schadenfreude, an example of a word so good that English simply imported it. Yes, we English speakers are word banditos.

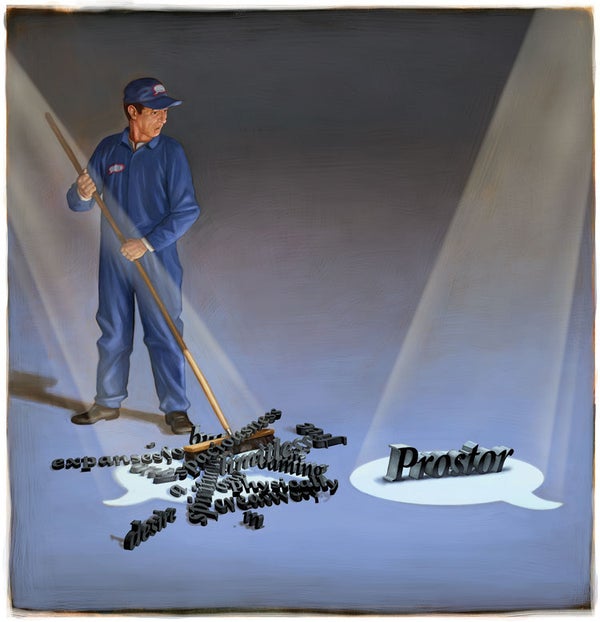

I had no idea until I read Lomas that I had many times engaged in gökotta. That's Swedish for waking up early to go outside to hear the morning's first birds sing. In the right setting, gökotta can help fulfill your prostor. That's the Russian word Lomas's paper cites as capturing “a desire for spaciousness, roaming free in limitless expanses, not only physically, but creatively and spiritually.” You might concurrently achieve Waldeinsamkeit, German for the mysterious, and possibly slightly creepy, solitude available when alone in the woods.

Once your Wanderlust is quenched, you can contribute to Lomas's research. Just go to www.drtimlomas.com/lexicography to add any “untranslatable” words he has yet to uncover. It might even be good for your karma.