Abstract

Forest fires are a major contributor of atmospheric gaseous and particulate pollutants. With respect to forest fires, Greece faces one of Europe’s most severe problems during summer. To create a forest fire emissions inventory, a database which holds data for forest fires in Greece during the period 1997–2003 was established in this study and a methodology for the quantification of both gaseous and particulate matter emissions from forest fires was developed. The contribution of forest fire pollutant emissions to the total anthropogenic and natural emissions in Greece has been estimated in detail for a specific period during July 2000 when widespread forest fires occurred in the Greek mainland. The mesoscale air quality modeling system UAM-AERO was used to quantify the contribution of forest fire emissions to the air pollution levels in Greece, and it was calculated that the forest fire emissions were the largest contributors to the air pollution problem in regions tens of kilometers away from the fire source during this period. The wildfire emissions were calculated to cause an increase in the average PM10 concentration, organic aerosol mass, and gaseous concentration of several pollutants, among them CO, NO x , and NH3. An average contribution of 50% to the PM10 concentration over the region around the burnt area and downwind of the fire source (approximately 500 km) is calculated with a maximum of 80%, whereas, for CO, the average contribution was 50% during this period. The theoretical calculations were compared with in situ observations of smoke aerosols captured by a backscatter lidar system over the Greater Athens Basin as well as with surface observations of NO2 and O3 and the calculated concentrations were in better agreement with observations when forest fire emissions were included in the model calculations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In forest fires are emitted significant amounts of gaseous and particulate matter pollutants into the atmosphere. Forest fires can play a significant role in atmospheric chemistry and contribute to climate change (Luterbacher et al. 2004; MacCracken et al. 1986; Penner et al. 1991; Stohl et al. 2007; UCAR 1986). Stohl et al. (2007) showed that agricultural fires in Eastern Europe can significantly alter the air pollution levels in the European Arctic. Forest fires can affect the physicochemical properties of the atmosphere, via the release of significant amounts of particulate matter, which interact with solar radiation (Andreae 1991; Andreae and Merlet 2001; Holben et al. 1991; Pace et al. 2005; Trentmann et al. 2005). Black carbon, for example, absorbs solar radiation strongly (Martins et al. 1998), and biomass burning is responsible for as much as 45% of the emissions of black carbon on a global scale (Andreae et al. 1996). Atmospheric particulate matter (PM) also acts as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN), which are important for the radiation balance and the hydrological cycle. Future climate warming may enhance the occurrence and impact of forest fires on regional air quality (Schar et al. 2004).

Forest fire emissions can be important for local air pollution levels (IPCC 2007; Sandberg et al. 1978). According to the CORINAIR-1990 inventory, forest fires contribute 0.2% to the emissions of NO x , 0.5% to the emissions of nonmethane volatile organic compounds, 0.2% to the emissions of CH4, 1.9% to the emissions of CO, 1.2% to the emissions N2O, and 0.1% to the emissions of NH3 in Europe (EMEP/CORINAIR 2002). As these emissions are constrained to short time periods and limited areas, the impact is more severe for public health [such as respiratory symptoms and illnesses including bronchitis, asthma, pneumonia and upper respiratory infection, impaired lung function, and cardiac diseases (Bowman and Johnston 2005; EC 1997)].

Unlike other anthropogenic sources, forest and agricultural biomass fire emissions are poorly quantified in the literature due to the difficulties in estimating their temporal and spatial distribution (Andreae 1991; Dennis et al. 2002; Hays et al. 2005; Junquera et al. 2005). Furthermore, the smoke production can vary by an order of magnitude or more from year to year (Andreae 1991). The process of burning consists of many stages, producing different compounds at each one of them, while the burnt material is inhomogeneous and difficult to describe in mathematical terms. This fact may cause significant differences between predicted and observed levels of air pollution.

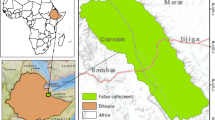

In the current paper, the focus is on the construction of an emission inventory from forest fires in Greece for the period 1997–2003 in conjunction with a modeling study to quantify the effect on air quality from extensive forest fires in the Greek mainland during July 2000. Greece faces one of Europe’s most severe problems concerning forest fires. Forests, partly forested areas, brush lands, and pastures cover approximately the two thirds of Greece (131,957 km2) (Dimitrakopoulos 1994). Each year, the area burnt in Greece is larger than 10% of the total burnt forested area in South Europe (European Communities 2001). The total area burnt per fire event in Greece is larger than anywhere else in Europe. It has been estimated that 0.394 km2 is burnt in every forest fire in Greece compared to 0.300 km2 in Spain, 0.200 km2 in Italy, and 0.153 km2 in Portugal (Dimitrakopoulos 1990).

Materials and methods

Quantification of forest fire emissions

In this study, we quantified gaseous and particulate matter emissions from forest fires in Greece. The pollutants studied are the main products of forest fires: CO2, CO, nonmethane hydrocarbons (NMHCs: C3H6, C2H2, C2H2, C3H8, n-C4H10), particulate matter (as TSP), nitrogen compounds (NO2, NH3, N2O), and sulfur compounds (mostly SO2). Also emitted from forest fires are species such as H2, COS, and CH3Cl which are not studied further as they are of minor importance to tropospheric chemistry even though their consequences to the stratosphere are not negligible (Andreae 1991). In particular, we estimated the forest fire emissions for the period 12–16 July 2000 during which widespread forest fires occurred in the Greek mainland. In this context, a database which holds data on forest fires in Greece during the period 1997–2003 was created. The database contains data for the time and location of fire, duration, area, and type of vegetation burnt which were obtained from the Ministry of Rural Development and Foods, General Directorate for Development and Protection of Forests and Natural Environment in Greece. The emissions of the main pollutants produced during forest fires were then calculated and integrated in emission inventories of anthropogenic and natural occurring emissions (Aleksandropoulou and Lazaridis 2004).

The quantification of emissions during forest fires was performed in the following steps: (1) estimation of the biomass burnt, (2) estimation of the total carbon emitted, (3) calculation of the emissions of carbon compounds (CO2, CH4, CO, NMHCs), (4) estimation of the total nitrogen emitted, (5) calculation of the emissions of nitrogen compounds, (6) calculation of the emissions of sulfur compounds (SO2), (7) estimation of the total suspended particulate matter (TSP) emitted, and (8) redistribution of the TSP regarding their size and chemical composition.

The estimation of the burnt biomass is rather complicated as it depends on many parameters. The burning material is inhomogeneous, adding complexity to the emission estimates. Forest fire fuels include all the materials that can be affected by a fire such as shrubs, trees, leaves, branches, barks, and all the organic matter that is present in the upper layers of the ground. In particular, the amount of the dry biomass burnt (M in kilograms) is estimated after Seiler and Crutzen (1980):

where A is the area burnt (in square meters), B is the mean biomass quantity per area unit (in kilograms per square meter), a is the fraction of biomass above the surface, and b is the burning efficiency of the vegetation which exists above the ground. The coefficients B, a, and b depend on the type of the ecosystem (dimensionless). The classification used in the present study is based on the studies of Seiler and Crutzen (1980) and EMEP/CORINAIR (2002). The burnt biomass per area unit (in kilograms per square meter) has a value of 2.81 for Mediterranean forest, 2.40 for scrubland, and 0.36 for grassland (EMEP/CORINAIR 2002; Seiler and Crutzen 1980).

The main carbon compounds emitted from a forest fire are carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, methane, and hydrocarbons. The quantity of carbon emitted (in kilograms) is estimated as:

where 0.45 is the mean mass fraction of carbon in dry biomass (with mass M in kilograms) and is considered independent of the type of biomass.

The emissions of carbon compounds (E j ) are calculated using the following expression:

where j is the compound, ɛ j is the portion of the total carbon emitted as compound j, and δ j is the conversion factor from emissions in C equivalent to emission in mass of single compounds (in tons). The average molecular weight of NMHCs is assumed equal to 37 g/mol following the speciation of Radke et al. (1991): 35% C3H6, 30% C2H2, 16% C2H2, 14% C3H8, 5% n-C4H10 (by mass).

The nitrogen compounds used in the present study is nitrogen dioxide, nitrogen protoxide, and ammonia. The emitted nitrogen mass (in kilograms) is estimated by:

where 0.0045 is the mass fraction of nitrogen in dry biomass (with mass M in kilograms) and is assumed to be the same for all species. The emissions (in kilograms) of the nitrogen compounds are:

where j is the compound, ɛ j is the fraction of total nitrogen emitted as compound j, and δ j is the conversion factor from emissions in N equivalent to emissions in mass of single compounds (in tons). The values of factors ɛ j and δ j for each vegetation species are taken from Trozzi et al. (2002) and EMEP/CORINAIR (2002).

The main sulfur compound emitted from forest fires is sulfur dioxide. The mass of SO2 emitted (in kilograms) is estimated by:

Finally, the total mass of particulate matter emitted from forest fires (in kilograms) is found from:

where 0.0085 is the mass fraction of total suspended particulate matter (TSP) of dry biomass (M in kilograms) (US EPA 1995). The calculated PM emissions are distributed in nine size bins: (1) d p ≤ 0.08, (2) 0.08 < d p ≤ 0.16, (3) 0.16 < d p ≤ 0.31, (4) 0.31 < d p ≤ 0.62, (5) 0.62 < d p ≤ 1.25, (6) 1.25 < d p ≤ 2.50, (7) 2.50 < d p ≤ 5.00, (8) 5.00 < d p ≤ 10.0, and (9) d p ≥ 10 (d p is the aerodynamic mass diameter in micrometers). Particulate matter emissions, which are made up mainly of organic and elemental carbon, were chemically resolved after Lurmann et al. (1997).

Model description and initialization/modeling approach

In the current work, concentrations of aerosols and gaseous pollutants were modeled using the UAM-AERO mesoscale modeling system (STI 1996). Two separate simulations were performed; one including anthropogenic, natural, and forest fire emissions (scenario I) and one including only forest fire emissions (scenario II). The simulations were carried out to quantify the contribution of the forest fire emissions to the ambient concentration of aerosols and gaseous pollutants.

The UAM-AERO mesoscale model is a gas/aerosol air quality model that is based on the model UAM version IV (Lurmann et al. 1997) and it is designed to simulate the atmospheric processes governing ambient concentrations of both gaseous pollutants and particulate matter. The model simulates the effects of emissions, horizontal and vertical transport and dispersion, chemical reactions, and dry deposition on atmospheric concentrations of pollutants. The UAM-AERO model incorporates a chemically resolved aerosol model with the major primary and secondary particulate matter components including elemental and organic carbon (OC), sulfate, nitrate, ammonium, water, sodium, chloride, and crustal material. Internally mixed aerosol is assumed and, at each particular particle size, the aerosol has the same chemical composition. Condensable organics are simulated using the yields reported by Pandis et al. (1992). Production of sulfuric acid from aqueous phase oxidation was also included. Gas/aerosol equilibrium is computed using the SEQUILIB algorithm (Pilinis and Seinfeld 1987).

The UAM-AERO model allows the use of various alternative chemical mechanisms. The one employed for this case study was the carbon bond-IV (CB-IV) where species are lumped according to the type of their C–C bonds. A large number of reactions, involving 47 species were taken into account. In addition, several modifications were introduced in the UAM-AERO mesoscale model compared to the standard UAM-IV model, including new preprocessors for biogenic and natural emissions (Aleksandropoulou and Lazaridis 2004; Spyridaki et al. 2006), new deposition routines, and inorganic equilibrium chemistry module. Moreover, gas-to-particle conversion routines were included for treating secondary formed inorganic and organic aerosols (Lurmann et al. 1997).

During a forest fire, there is a large positive heat flux at the surface leading to very unstable conditions in the atmosphere and a deeper boundary layer. An algorithm developed to account for these conditions is adopted in the current work (Gurer and Georgopoulos 2001).

The model was applied over a domain (58 × 74 grid points of area 10 × 10 km2) which covers all of the Greek mainland, most of the islands, and parts of the contiguous countries with five vertical layers, two below and three above the diffusion break. Topography and land use data were obtained from previous studies (Aleksandropoulou and Lazaridis 2004). The meteorological inputs were obtained using a numerical weather prediction (NWP) model with an extended treatment of clouds and precipitation. This model is based on the limited-area model NORLAM from the Norwegian Meteorological Institute (Grønaas et al. 1987; Nordeng 1986). The cloud process extensions are developed at the University of Bergen and documented in Sundqvist (1998), Sundqvist et al. (1989), and Kvamstø (1992).

Annular anthropogenic emission inventories for gaseous species and aerosols were derived from the UNECE/EMEP database (EMEP/CORINAIR 2002; Webdab 2002). The dataset includes also gaseous emissions from ships (local and international sea traffic; Lavender 1999). The methodology for the spatial mapping of anthropogenic emissions and the estimation of biogenic and natural occurring emissions was presented by Aleksandropoulou and Lazaridis (2004). Temporal allocation of emissions was computed based on the seasonal, day-to-day, and day–night variation of emission factors (EMEP-MSC/W 2003; Spyridaki et al. 2006).

The emissions of gaseous and particulate matter pollutants from forest fires were estimated using the emission methodology presented above. The location of the forest fires in the forest fire database is given in latitude–longitude of the starting point of each fire. The spreading of the forest fire was assumed to follow an ellipsoidal pattern with the major axis along the wind direction and with the fire in one of the foci of the ellipse (e.g., Anderson et al. 1982; Andrews and Chase 1989; Arora and Boer 2005; Richards 1990). In this way, the burnt areas were transferred to the grid used in the present study. Also, the forest fires were separated to study each fire as many hourly events depending on their duration.

Initial and boundary conditions for the gaseous species were obtained from the NILU-CTM model (Flatøy et al. 2000) and on particulate matter from the EMEP model (ApSimon et al. 2001).

Results and discussion

Forest fire emissions

The historical trend in wildfires in Greece is presented in Table 1. Data presented for the period 1960–1996 are derived from Dimitrakopoulos (1994) and Xanthopoulos (1997). The data for the period 1997–2003 are calculated based on data provided by the Greek Ministry of Rural Development and Foods. The mean area burnt per fire event raised from 0.17 km2 during the decade 1960–1969 to 0.20 km2 (1970–1979) and 0.39 km2 (1980–1989) (Dimitrakopoulos 1994). During the period 1990–1999, the mean area burnt per fire dropped to 0.28 km2. Changes may be attributed to variable meteorological conditions and differences in extensive dry conditions during summer. In addition, a downward trend in the total area burnt per year has been noticed during the last decade. However, it is depicted that, during the year 2000, the area burnt was the largest of the past 40 years.

The total number of fires in Greece during the year 2000 was 1,469 and the total area burnt was 991.7 km2. Of the total area burnt by forest fires, more than 0.5 km2 was burnt by individual fires in 86% of the cases. Specifically, in July 2000, 269 wildfires were recorded in Greece with a total area burnt of 626 km2. Forest fires emissions are considered to be of anthropogenic nature because 94% of the forest fires during the study period were man made as indicated in the report of the Ministry of Rural Development and Foods, General Directorate for Development and Protection of Forests and Natural Environment in Greece. The mean duration of each forest fire was found to be about 48 h during July 2000. It is also important to notice that 28 forest fires lasted for more than 1 week.

The long duration of the forest fires resulted in a large area burnt per fire event. Fifty-three forest fires burnt more than 1 km2 each (data not shown). The onset and spreading of a forest fire depends on the type of vegetation. The vegetation types used in the present study were Mediterranean forests, scrubland, and grassland. Using these categories and the methodology described above, the biomass burnt during July 2000 was estimated to be about 1.5 Mt.

The emissions of gaseous and particulate matter pollutants were estimated using the emission methodology presented above. The total emissions of gaseous and particulate matter pollutants under study during July 2000 are presented in Table 2. The anthropogenic emissions are derived from EMEP-MSC/W, Inventory Review (2004) (gaseous compounds), EMEP (2002), and EMEP-MSC/W (2002). It is observed that pollutant emissions from forest fires make up a considerable fraction of the total emissions in Greece. Their contribution varies from 1% to 22% with the greater values found for particulate matter (22%) and carbon monoxide (17.3%) and the lower values for SO2 (0.3%) and N2O (0.9%). Emissions of HCs account for the 15% of the total anthropogenic emissions, CH4 and NH3 3%, and NO2 1.5% of the national total during July 2000.

In July 2000, the more severe (as regards the total area burnt) forest fire events occurred during the period 10–16. The UAM-AERO mesoscale model was run for the forest fire episodes during the period 12–16 July. During this period, the emissions of particulate matter and several gaseous pollutants from forest fires on the local scale (focus on the burnt area only) were significantly greater than the total anthropogenic emissions. The ratio between emission rates from forest fires to those from other anthropogenic activities ranged from 6 × 102 to 1.8 × 105 for OC and between 2 × 102 and 6 × 104 for elemental carbon. High ratios were also estimated for CO (between 5 × 102 and 7 × 103), SO2 (between 1 × 101 and 4 × 102), NH3 (between 1 × 102 and 8.5 × 102), and NO2 (between 1 × 103 and 1.1 × 103).

Verification/validation of model results

The UAM-AERO model was applied to model summer forest fire events between 12 and 16 July 2000. The occurrence of large forest fires in the Greek mainland during this period is documented from air quality and lidar measurements and satellite images (Balis et al. 2003; Eleftheriadis et al. 2005; Sciare et al. 2003; Smolik et al. 2003). In particular, satellite pictures (captured by the NOAA Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite [GOES] sensor) provide evidence for long-range transport of the forest fire emissions above Greece. The forest fire plume originating at the northern Peloponnesus (west of Athens) passing over the Greater Athens Area (GAA) and extending to the central Aegean Sea and Turkey on 13 July 2000 (14:42 UTC) is shown in Fig. 1. The geographical pattern of the fire plume was calculated with the UAM-AERO model (e.g., in Fig. 9a,b, the concentrations of fine particles and CO resulting from forest fires only are depicted) and is in agreement with the satellite image.

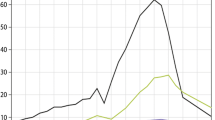

The transport of the fire plume over GAA was evident in gaseous compounds concentration measurements in Athens and at the vertical profile of PM10 obtained by lidar measurements during the period of simulation. In particular, Fig. 2 shows the calculated surface layer concentration of NO2 and O3 in the GAA as a function of time during the period 13–16 July 2000 for scenarios I and II together with their measured concentration at urban and suburban background stations in Athens. Urban background data were collected at the “Nea Smirni” station (EEA’s EuroAirnet network station code 105) and suburban background data at the “Lykovrisi” station (EEA’s EuroAirnet network station code 102) from the airbase of EEA. Measurements of ozone and NO2 at surface stations were made on an hourly basis throughout the period (Fig. 2a,b). The surface measurements from Athens for NO2 and O3 compared with the calculations (Fig. 2a,b) show that the calculated concentrations are lower than the observed NO2 concentrations in the Athens Metropolitan Area and in qualitative agreement with the measurements. For ozone, the calculated concentrations are much lower than the observed ones while the diurnal variation is in agreement (Pearson R for suburban and urban background stations is 0.5 and 0.6, respectively; Fig. 2b). The elevated ozone concentrations observed at the suburban background station in the Athens Greater Area on 13 July is not observed in the calculations. Also, in other pollutant events arising from biomass fire emissions, it has turned out to be difficult to reproduce the observed ozone concentrations in the smoke plume several days downwind of the source (Stohl et al. 2007).

Observed a NO2 and b O3 concentrations at the surface at an urban and a suburban measurement site in the GAA. In addition, the calculated concentrations in the lowest model layer for the period 13–16 July 2000 over the GAA for the two scenarios (scenario I, all emission sources included; scenario II, only forest fire emissions included) are presented

In addition, laser range-resolved (lidar) measurements of the aerosol vertical profile were performed on 13 July 2000, over the GAA by a single backscattering system (Papayannis and Chourdakis 2002) at 532 nm (Fig. 3a). The vertical profile of the aerosol backscatter coefficient β aer(z) (Weitkamp et al. 2005) is shown at 15:00–17:00 UT from 0.5 to 4.5 km above sea level. The smoke layer has a multistructural profile and is mainly visible around 15:00 UT between 2 and 3.5 km height. Later (between 16:00 and 17:00 UT), it was less pronounced and moved from the source area to the Aegean Sea, as also captured by the NOAA GOES sensor (Fig. 1; satellite data). Backtrajectories calculated using the HYSPLIT-4.6 code (Draxler and Rolph 2003; Rolph 2003) for the air masses ending at 15:00 UT over the GAA area on 13 July at 2,000 and 3,000 m, the height where the lidar observed the smoke plume, are shown in Fig. 4. These air masses passed over the forest fires a few hours earlier.

a Aerosol vertical profile (aerosol backscatter coefficient) obtained by a single elastic lidar system at 532 nm over Athens between 15:00 and 17:00 UT 13 July 2000. b Calculated PM10 vertical profile 16:00–19:00 UT above the Athens metropolitan area resulted (scenario II, forest fire emissions only)

The vertical profiles of PM10 calculated with the UAM-AERO model between 16:00 and 19:00 UT for the Athens metropolitan area are shown in Fig. 3b. There are two maxima in the calculated profiles, at 1 km and another close to 3.5 km. The calculated maximum concentration above 1.5 km is found at 18:00 UT, but the calculated profile did not reproduce the observed maximum at 3 km seen in Fig. 3a. The time of passage of the smoke plume across the GAA was approximately the same in the observed profile and the calculated one, however. The model did not reproduce the observed vertical aerosol profile well around the time of its maximum. The lifting of the forest fire PM emissions to the lower free troposphere is underestimated in the calculations, and the coarse vertical resolution in the model introduces too rapid mixing.

Contribution of forest fire emissions to air quality in Greece

The simulations were carried out using the UAM-AERO model to quantify the contribution of the forest fire emissions to the ambient concentration of aerosols and gaseous pollutants. We concentrate mainly on the impact of forest fire emissions on the air quality at the surface level (first layer of the UAM-AERO model) in Greece.

The contribution of forest fires emissions to the ambient concentrations of gaseous and aerosol pollutants is important on the regional scale as also shown in other studies (Junquera et al. 2005; Stohl et al. 2007). The contribution of the forest fire emissions was calculated by comparison with simulations of gaseous and aerosol pollution levels over the GAA performed with the two different scenarios. In particular, the calculated concentration of CO reached values close to 450 ppb (maximum contribution ∼30%; Fig. 5a) based on forest fire emissions only (scenario II) on 14–15 July and with the same emission assumptions NO2 approached 10 ppb (maximum contribution ∼38%; Fig. 2a). The contribution to PM10 from the forest fire emissions was calculated to exceed 30 μg/m3 at times (maximum contribution ∼44%; Fig. 5b). The contribution to ozone from the forest fire emissions is calculated to be quite small (maximum contribution ∼19%; Fig. 2b), although the scenario II calculation in this case is not reliable since the formation and concentration of ozone depends in a nonlinear way on the precursor concentrations. However, the measured data showed an increased level of O3 which corresponds to the elevated PM levels observed by lidar on 13 July.

In addition, the contribution of the forest fire emissions was calculated by comparison with simulations of gaseous and aerosol pollution levels in the eastern Mediterranean without the forest fire emissions, as performed by Lazaridis et al. (2005) and Spyridaki et al. (2006). In this case, the average fine particulate matter concentration in the southeastern part of the modeled area were less than about 2 μg/m3 while it exceeded 20 μg/m3 during the forest fire events (scenario II; Fig. 7).

Figures 6 and 7 show the spatial distribution of organic mass (OM) in the particulate phase (where OM = 1.4∙OC; Quinn et al. 2000) and PM2.5, respectively, as derived from model simulations including only the emissions from the forest fire events on 14 July 2000 (scenario II). The surface concentration fields of NO2, NH3, and CO for the same scenario (II) are shown in Fig. 8. These pollutants are representative of the forest fire emissions. The surface concentrations at 1 a.m. on 14 July 2000 are shown in Figs. 6 and 7, while the fields in Fig. 8 are taken at 1 a.m. on 13 July 2000. The calculations illustrate the combined effect of chemical transformation and dispersion of the forest fire emissions. The contribution of forest fires to the fraction of organic matter in PM10 (Fig. 6) exceeded 2 μg/m3 more than 500 km from the forest fire sources, while to the concentration of fine aerosols (PM2.5) (Fig. 7) reached 20 μg/m3, 10 ppb to NO2, 0.5 ppb to NH3, and 100 ppb to CO concentrations (Fig. 8).

Figure 9 shows the surface concentration maps of fine particles (PM2.5) and carbon monoxide that originated from the forest fires as simulated by the UAM-AERO model (scenario II, only forest fire emissions). The contribution of forest fire emissions to the PM2.5 concentrations over the burnt area reached values was close to 15 μg/m3, whereas for CO concentrations, the maximum contribution inside the plume (areas downwind of the fire sources) was above 100 ppb. The simulation results show the same geographical smoke pattern as the satellite picture giving a qualitative agreement between model results and satellite observations (Fig. 1).

The contribution of the forest fire emissions to the ambient particulate matter and gaseous species concentrations in Greece is calculated by comparing the results of the runs of scenarios I and II. The contribution (percentage) of forest fire emissions to the CO concentrations in the lowest model layer on 18:00 p.m. 13 July is shown in Fig. 10. The contribution of forest fire emissions to the CO concentration in the lowest model layer (surface) is more than 50% over the areas affected by the fire plumes (the maximum contribution was approximately 80%) at this time, indicating that the forest fires make large contributions to ambient CO. Figure 10 demonstrates the regional character of the forest fire emission contribution to elevated CO levels over a large portion of the Aegean Sea and parts of Turkey.

The percentage contribution of forest fires emissions (scenario II) to the total concentration of particulate matter (scenario I) in the lowest model layer on 13 July at 18:00 p.m. (15:00 UTC) is shown in Fig. 11 . The average forest fire emission contribution to PM10 is around 50% (with maximum values reaching 75%) over areas tens of kilometers away from the fire source which are affected by the smoke plume at this time. In addition, for fine particles, the forest fire emission contribution averages 70% (maximum ∼87%) in line with the emission profiles of particles from forest fires. The contribution from forest fire emissions to the ambient concentration of coarse particles is around to 10% (maximum ∼31%) in the areas receiving the smoke plumes on 13 July at 18:00 p.m.

Finally, the change in the particulate matter size distribution due to the forest fire events on 13 July is shown in Fig. 12. The distributions presented in Fig. 12 refer to the results from the model simulation including all anthropogenic and natural emissions but not including forest fires (Spyridaki et al. 2006) and to the simulation including all emissions in the model domain (scenario I–total). The distributions refer to the average PM10 levels calculated for the lowest model layer in the Athens metropolitan area (37°58′ N, 23°43′ E) during the period of lidar measurements (Fig. 4) where the passage of the smoke over the Athens area was identified. The forest fires contributed significantly to the ambient PM10 levels and changed the shape of the size distribution. The forest fire emissions gave rise to a considerable increase in the fine fraction of the size distribution with an increase of the ultrafine to coarse ratio from about 0.40 to 0.80 as shown in Fig. 12.

Conclusions

A database of the forest fires in Greece, for the years 1997–2003, has been created. A downward trend in the total area burnt per year has been noticed during the last decade. The maximum area burnt occurred in 2000. Based on the above database, a methodology for the estimation of gaseous and particulate pollutants was developed. The speciation and quantification of the emissions depends on the type of vegetation. The air pollution load at a certain location is related to the time and space evolution of the fire event and the meteorological conditions, factors which influence the amount of pollutants emitted and the degree of dispersion of the plume.

Forest fire simulations were performed using the UAM-AERO air quality model in conjunction with the forest fire emission inventories developed in this study. The simulation period coincided with the period of maximum burnt area (13–16 July 2000).

The simulations performed have shown that the impact of the forest fire emissions on air quality during the period 13–16 July 2000 exceed the impact of anthropogenic pollution close to the forest fire sources (approximately 500 km downwind of the forest fire source). Forest fire emissions have significant buoyancy due to the heat that develops while burning which together with the regional winds are spreading the emissions and their products over a large area that exceeds the region of Greece. There is a strong regional transport aspect of forest fire events. Forest fires have been found to increase the ambient level of CO, NO2, NH3, and particulate matter. An average contribution to the PM10 concentration of 50% has been calculated over the areas receiving the smoke plumes. Forest fires cause an increase mainly in the ambient concentration of fine particles over the areas receiving the smoke plumes (average contribution of 70%), whereas for coarse particles, the corresponding number is small (contribution of 10%).

The smoke aerosol plume was forecasted by our model and observed over the GAA by a single elastic lidar system at 532 nm. Evaluation of the simulations’ results via comparison with experimental data in future studies could help toward an optimization of the emission factors used.

References

Aleksandropoulou V, Lazaridis M (2004) Spatial distribution of gaseous and particulate matter emissions in Greece. Water Air Soil Pollut 153:15–34 doi:10.1023/B:WATE.0000019923.58620.58

Anderson DH, Catchpole EA, DeMestre NJ, Parkes T (1982) Modelling the spread of grassland fires. J Aust Math Soc Series B 13:452–466

Andreae MO (1991) Biomass burning: its history, use and distribution and its impact on environmental quality and global climate. In: Levine JS (ed) Global biomass burning: atmospheric, climatic and biospheric implications. MIT, MA, pp 3–21

Andreae MO, Merlet P (2001) Emission of trace gases and aerosols from biomass burning. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 15(4):955–966 doi:10.1029/2000GB001382

Andreae MO, Atlas E, Cachier H, Cofer WR, Harris GW, Helas G, Koppmann R, Lacaux JP, Ward DE (1996) Trace gas and aerosol emissions from savanna fires. In: Levine JS (ed) Biomass burning and global change, vol. 1: remote sensing, modeling and inventory development, and biomass burning in Africa. MIT, MA, pp 278–295

Andrews PL, Chase CH (1989) BEHAVE: fire behavior prediction and fuel modeling system—burn subsystem, part 2. General Technical Report INT-260, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service

ApSimon HM, Gonzalez del Campo MT, Adams HS (2001) Modelling long-range transport of primary particulate material over Europe. Atmos Environ 35:343–352 doi:10.1016/S1352-2310(00)00143-6

Arora VK, Boer GJ (2005) Fire as an interactive component of dynamic vegetation models. J Geophys Res 110:GO2008 doi:10.1029/2005JG000042

Balis B, Amiridis V, Zerefos C, Gerasopoulos E, Andreae M, Zanis P, Kazantzidis A, Kazadzis S, Papayannis A (2003) Raman lidar and sun-photometric measurements of aerosol optical properties over Thessaloniki during a biomass burning episode. Atmos Environ 37:4529–4538 doi:10.1016/S1352-2310(03)00581-8

Bowman DMJS, Johnston FH (2005) Wildfire smoke, fire management, and human health. EcoHealth 2(1):76–80 doi:10.1007/s10393-004-0149-8

Dennis A, Fraser M, Anderson S, Allen DT (2002) Air pollutant emissions associated with forest, grassland and agricultural burning in Texas. Atmos Environ 36:3779–3792 doi:10.1016/S1352-2310(02)00219-4

Dimitrakopoulos AP (1990) A synopsis of the Greek wildland fire problem. Int For Fire News 4:6–7

Dimitrakopoulos AP (1994) The 1993 Forest Fire Season in Greece Statistics Report. Int For Fire News 10:11–12

Draxler RR, Rolph GD (2003) HYSPLIT (HYbrid single-particle Lagrangian integrated trajectory). Model access via NOAA ARL READY website, NOAA Air Resources Laboratory, Silver Spring, MD. Available at http://www.arl.noaa.gov/ready/hysplit4.html

Eleftheriadis K, Colbeck I, Dye C, Housiadas C, Lazaridis M, Mihalopoulos N, Mitsakou C, Smolik J, Zdimal V (2005) Size distribution, composition and origin of the submicron aerosol in the marine boundary layer during the eastern Mediterranean “SUB-AERO” experiment. Atmos Environ 40:6245–6260 doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.03.059

EMEP/CORINAIR (2002) Atmospheric emission inventory guidebook, 3rd edn. EEA Technical Report No. 30, EMEP Task Force on Emission Inventories

EMEP-MSC/W (2002) First estimates of the effect of aerosol dynamics in the calculation of PM10 and PM2.5. EMEP Summary Report, Note 4/2002

EMEP-MSC/W (2003) Transboundary acidification and eutrophication and ground level ozone in Europe: unified EMEP model description, part I. EMEP-MSC/W Report, Note 1/2003

EMEP-MSC/W, Inventory Review 2004 (2004) Emission Data reported to CLRTAP and under the NEC Directive. EMEP/EEA Joint Review Report, Note 1/2004

European Commission (1997) Technical working group on particles: ambient air pollution by particulate matter. Draft Position Paper 1997(8)

European Communities (2001) Forest fires in southern Europe: bulletin of the 2000 fire campaign. Report No. 1, SPI 01.95, p 40

Flatøy F, Hov Ø, Schlager H (2000) Chemical forecasts used for measurement flight planning during the POLINAT 2. Geophys Res Lett 27:951–954 doi:10.1029/1999GL010805

Grønaas S, Foss A, Lystad M (1987) Numerical simulations on polar lows in the Norwegian Sea. Tellus 39A:224–353

Gurer K, Georgopoulos PG (2001) A coupled forest fire emission and atmospheric dispersion model: an application to the Savannah River Site (SRS). Technical Report. Available at http://www.ccl.rurgers.edu

Hays MD, Fine PM, Geron CD, Kleeman MJ, Gullett BK (2005) Open burning of agricultural biomass: physical and chemical properties of particle-phase emissions. Atmos Environ 39:6747–6764 doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.07.072

Holben BN, Kaufman YJ, Setzer AW, Taure DD, Ward DE (1991) Optical properties of aerosol emissions from biomass burning in the tropics, BASE-A. In: Levine JS (ed) Global biomass burning: atmospheric, climatic and biospheric implications. MIT, MA, pp 403–411

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2007) Summary for policymakers. In: Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M, Averyt KB, Tignor M, Miller HL (eds) Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, New York

Junquera V, Russell MM, Vizuete W, Kimura Y, Allen D (2005) Wildfires in eastern Texas in August and September 2000: emissions, aircraft measurements, and impact on photochemistry. Atmos Environ 39:4983–4996 doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.05.004

Kvamstø NG (1992) Implementation of the Sundqvist Scheme in the Norwegian limited area model. Meteorological report series 2–92. University of Bergen, Norway

Lavender KA (1999) Marine exhaust emissions, quantification study—Mediterranean Sea. Final Report 99/EE/7044, Lloyds Register of Shipping, UK

Lazaridis M, Spyridaki A, Solberg S, Smolik J, Zdimal V, Eleftheriadis K, Aleksandropoulou V, Hov Ø, Georgopoulos PG (2005) Mesoscale modelling of combined aerosol and photooxidant processes in the eastern Mediterranean. Atmos Chem Phys 5:927–940

Lurmann FW, Wexler AS, Pandis SN, Mussara S, Kumar N, Seinfeld JH (1997) Modelling urban and regional aerosols—II. Application to California’s South Coast Air Basin. Atmos Environ 31:2695–2715 doi:10.1016/S1352-2310(97)00100-3

Luterbacher J, Dietrich D, Xoplaki E, Grosjean M, Wanner H (2004) European seasonal and annual temperature variability, trends, and extremes since 1500. Science 303:1499–1503 doi:10.1126/science.1093877

MacCracken MC, Cess RD, Potter GR (1986) Climatic effects of anthropogenic arctic aerosols: an illustration of climatic feedback mechanisms with one- and two-dimensional climate models. J Geophys Res 91:14445–14450 doi:10.1029/JD091iD13p14445

Martins VJ, Artaxo P, Liousse C, Reid JS, Hobbs PV, Kaufman YJ (1998) Effects of black carbon content, particle size, and mixing on light absorption by aerosols from biomass burning in Brazil. J Geophys Res 103(D4):32041–32050 doi:10.1029/98JD02593

Nordeng TE (1986) Parameterization of physical processes in a three-dimensional numerical weather prediction model. Norwegian Meteorological Institute. Technical Report 65, Oslo, Norway

Pace G, Meloni D, di Sarra A (2005) Forest fire aerosol over the Mediterranean basin during summer 2003. J Geophys Res 110:D21202 doi:10.1029/2005JD005986

Pandis SN, Harley RA, Cass GR, Seinfeld JH (1992) Secondary organic aerosol formation and transport. Atmos Environ 26A:2269–2282

Papayannis A, Chourdakis G (2002) The EOLE Project: a multiwavelength laser remote sensing (LIDAR) system for ozone and aerosol measurements in the troposphere and the lower stratosphere. Part II: aerosol measurements over Athens, Greece. Int J Remote Sens 23:179–196 doi:10.1080/01431160010025952

Penner JE, Ghan SJ, Walton JJ (1991) The role of biomass burning in the budget and cycle of carbonaceous soot aerosols and their climate impacts. In: Levine JS (ed) Global biomass burning: atmospheric, climatic and biospheric implications. MIT, Cambridge, pp 387–393

Pilinis C, Seinfeld JH (1987) Continued development of a general equilibrium model for inorganic multicomponent atmospheric aerosols. Atmos Environ 21:2453–2466 doi:10.1016/0004-6981(87)90380-5

Quinn PK, Bates TS, Coffman DJ, Miller TL, Johnson JE, Covert DS, Putaud JP, Neususs C, Novakov T (2000) Comparison of aerosol chemical and optical properties from the 1st and 2nd aerosol characterization experiments. Tellus Ser B Chem Phys Meterol 52:239–257 doi:10.1034/j.1600-0889.2000.00033.x

Radke LF, Hegg DA, Hobbs PV, Nance JD, Lyons JH, Laursen KK, Weiss RF, Riggan PJ, Ward DE (1991) Particulate and trace gas emissions from large biomass fires in North America. In: Levine JS (ed) Global biomass burning: atmospheric, climatic and biospheric implications. MIT, Cambridge, pp 209–224

Richards GD (1990) An elliptical growth model of forest fire fronts and its numerical solution. Int J Numer Methods Eng 30:1163–1179

Rolph GD (2003) Real-time Environmental Applications and Display sYstem (READY). NOAA Air Resources Laboratory, Silver Spring, MD. Available at http://www.arl.noaa.gov/ready/hysplit4.html

Sandberg DV, Pierovich JM, Fox DG, Ross EW (1978) Effects of fire on air. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report WO-9, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

Schar C, Vidale PL, Luthi D, Frei C, Haberli C, Liniger MA, Appenzeller C (2004) The role of increasing temperature variability in European summer heatwaves. Nature 427:332–336 doi:10.1038/nature02300

Sciare J, Bardouki H, Moulin C, Mihalopoulos N (2003) Aerosol sources and their contribution to the chemical composition of aerosols in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea during summertime. Atmos Chem Phys 3:291–302

Seiler W, Crutzen PJ (1980) Estimates of gross and net fluxes of carbon between the biosphere and the atmosphere from biomass burning. Clim Change 2:207–247 doi:10.1007/BF00137988

Smolik J, Zdimal V, Schwarz J, Lazaridis M, Havranek V, Eleftheriadis K, Mihalopoulos N, Colbeck I (2003) Size resolved mass concentration and elemental composition of atmospheric aerosols over the eastern Mediterranean. Atmos Chem Phys 3:2207–2216

Spyridaki A, Lazaridis M, Eleftheriadis K, Smolik J, Mihalopoulos N, Aleksandropoulou V (2006) Modelling and evaluation of size resolved aerosol characteristics in the Eastern Mediterranean during the SUB-AERO project. Atmos Environ 40:6261–6275 doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.03.058

Sonoma Technology, Inc. (STI) (1996) User’s guide to the UAM-AERO model. STI Report 12/1996

Stohl A, Berg T, Burkhart JF, Fjǽraa AM, Forster C, Herber A, Hov Ø, Lunder C, McMillan WW, Oltmans S, Shiobara M, Simpson D, Solberg S, Stebel K, Ström J, Tørseth K, Treffeisen R, Virkkunen K, Yttri KE (2007) Arctic smoke—record high air pollution levels in the European Arctic due to agricultural fires in Eastern Europe in spring 2006. Atmos Chem Phys 7:511–534

Sundqvist H (1988) Parameterization of condensation and associated clouds in models for weather prediction and general circulation simulations. In: Schlesinger ME (ed) Physically-based modelling and simulation of climate and climatic change, part I. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 433–462

Sundqvist H, Berge E, Kristjanson JE (1989) Condensation and cloud parameterization studies with a mesoscale NWP model. Mon Weather Rev 117:1641–1657 doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<1641:CACPSW>2.0.CO;2

Trentmann J, Yokelson RJ, Hobbs PV, Winterrath T, Christian TJ, Andreae O, Mason SA (2005) An analysis of the chemical processes in the smoke plume from a savanna fire. J Geophys Res 110:D12301 doi:10.1029/2004JD005628

Trozzi C, Vaccaro R, Piscitello R (2002) Emissions estimate from forest fires: methodology, software and European case studies. In: Proceedings of the 11th International Emission Inventory Conference, Atlanta, GA

United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) (1995) AP-42, compilation of air pollutant emission factors: volume I: stationary point and area sources, 5th edn. United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC

University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR) (1986) Global tropospheric chemistry: plans for the U.S. research effort. Office for Interdisciplinary Earth Studies, Boulder, CO

Webdab (2002) UNECE/EMEP WebDab emissions database 2002. Emissions as used in EMEP models. Emissions from Greece during 2000. Available at http://www.emep-emissions.at/emission-data-webdab/

Weitkamp C (2005) Lidar: range-resolved optical remote sensing of the atmosphere. Springer, New York

Xanthopoulos G (1997) The 1996 forest fire season. Int Forest Fire News. Bulletin No. 16

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the General Secretariat for Research and Technology of the Greek Ministry for Development, under grant “AEROMETRISI.” The contribution from the Norwegian Meteorological Institute was supported by the EU projects EUCAARI (FP6 European Integrated Project on Aerosol Cloud Climate and Air Quality Interactions) and CityZen (FP7 megaCITY—Zoom for the ENvironment). The authors gratefully acknowledge the NOAA Air Resources Laboratory (ARL) for the provision of the HYSPLIT transport and dispersion model (http://www.arl.noaa.gov/ready.html) used in this publication.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lazaridis, M., Latos, M., Aleksandropoulou, V. et al. Contribution of forest fire emissions to atmospheric pollution in Greece. Air Qual Atmos Health 1, 143–158 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-008-0020-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-008-0020-0